The Last Gospel

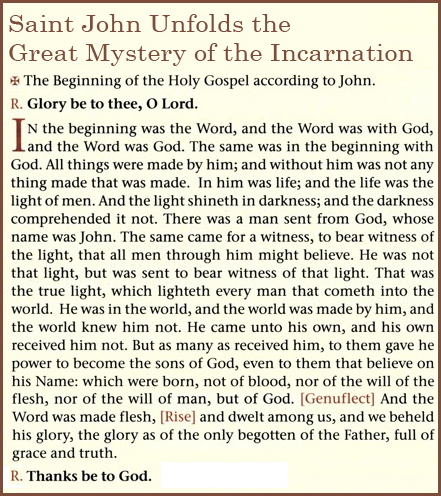

St John unfolds the great mystery of the Incarnation.

St John unfolds the great mystery of the Incarnation.

1: In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and

the Word was God. 2: He was in the beginning with God; 3: all

things were made through him, and without him was not anything

made that was made. 4: In him was life, and the life was the

light of men. 5: The light shines in the darkness, and the

darkness has not overcome it. 6: There was a man sent from God,

whose name was John. 7: He came for testimony, to bear witness to

the light, that all might believe through him. 8: He was not the

light, but came to bear witness to the light. 9: The true light

that enlightens every man was coming into the world. 10: He was

in the world, and the world was made through him, yet the world

knew him not. 11: He came to his own home, and his own people

received him not. 12: But to all who received him, who believed

in his name, he gave power to become children of God; 13: who were

born, not of blood nor of the will of the flesh nor of the will of

man, but of God. 14: And the Word became flesh and dwelt among

us, full of grace and truth; we have beheld his glory, glory as of

the only Son from the Father.

Commentary from The Navarre Bible, by the Faculty of Theology of

the University of Navarre.

These verses form the prologue or introduction to the Fourth Gospel;

they are a poem prefacing the account of Jesus Christ's life on earth, proclaiming

and praising his divinity and eternity. Jesus is the uncreated Word,

God the Only-begotten, who takes on our human condition and offers us the

opportunity to become sons and daughters of God, that is, to share in God's

own life in a real and supernatural way.

Right through his Gospel St John the Apostle lays special emphasis on our

Lord's divinity; his existence did not begin when he became man in Mary's

virginal womb: before that he existed in divine eternity as Word, one in

substance with the Father and the Holy Spirit. This luminous truth helps us

understand everything that Jesus says and does as reported in the Fourth Gospel.

St John's personal experience of Jesus' public ministry and his appearances

after the Resurrection were the material on which he drew to contemplate God's

divinity and express it as "the Word of God". By placing this poem as a prologue

to his Gospel, the Apostle is giving us a key to understand the whole account

which follows, in the same sort of way as the first chapters of the Gospels of

St Matthew and St Luke initiate us into the contemplation of the life of Christ

by telling us about the virgin birth and other episodes to do with his infancy;

in structure and content, however, they are more akin to the opening passages

of other NT books, such as Col 1:15-20, Eph 1:13-14 and 1 Jn 1-4.

The prologue is a magnificent hymn in praise of Christ. We do not know

whether St John composed it when writing his Gospel, or whether he based it

on some existing liturgical hymn; but there is no trace of any such text in other

early Christian documents.

The prologue is very reminiscent of the first chapter of Genesis, on a number

of scores: 1) the opening words are the same: "In the beginning..."; in the

Gospel they refer to absolute beginning, that is, eternity, whereas in Genesis

they mean the beginning of Creation and time; 2) there is a parallelism in the

role of the Word: in Genesis, God creates things by his word ("And God said

..."); in the Gospel we are told that they were made through the Word of God;

3) in Genesis, God's work of creation reaches its peak when he creates man in

his own image and likeness; in the Gospel, the work of the Incarnate Word

culminates when man is raised -- by a new creation, as it were -- to the dignity

of being a son of God.

The main teachings in the prologue are: 1) the divinity and eternity of the

Word; 2) the Incarnation of the Word and his manifestation as man; 3) the part

played by the Word in creation and in the salvation of mankind; 4) the different

ways in which people react to the coming of the Lord -- some accepting him

with faith, others rejecting him; 5) finally, John the Baptist bears witness to the

presence of the Word in the world.

The Church has always given special importance to this prologue; many

Fathers and ancient Christian writers wrote commentaries on it, and for centuries

it was always read at the end of Mass for instruction and meditation.

[Hence its title, "The Last Gospel".]

The prologue is poetic in style. Its teaching is given in verses, which combine

to make up stanzas (vv. 1-5; 6-8; 9-13; 14-18). Just as a stone dropped in a pool

produces ever widening ripples, so the idea expressed in each stanza tends to

be expanded in later verses while still developing the original theme. This kind

of exposition was much favoured in olden times because it makes it easier to

get the meaning across -- and God used it to help us go deeper into the central

mysteries of our faith.

1. The sacred text calls the Son of God "the Word." The following comparison

may help us understand the notion of "Word": just as a person becoming

conscious of himself forms an image of himself in his mind, in the same way

God the Father on knowing himself begets the eternal Word. This Word of God

is singular, unique; no other can exist because in him is expressed the entire

essence of God. Therefore, the Gospel does not call him simply "Word", but

"the Word." Three truths are affirmed regarding the Word -- that he is eternal,

that he is distinct from the Father, and that he is God. "Affirming that he existed

in the beginning is equivalent to saying that he existed before all things" (St

Augustine, De Trinitate, 6,2). Also, the text says that he was with God, that is,

with the Father, which means that the person of the Word is distinct from that

of the Father and yet the Word is so intimately related to the Father that he even

shares his divine nature: he is one in substance with the Father (cf. Nicean

Creed).

To mark the Year of Faith (1967-1968) Pope Paul VI summed up this truth

concerning the most Holy Trinity in what is called the Creed of the People of

God (n. 11) in these words: "We believe in our Lord Jesus Christ, who is the

Son of God. He is the eternal Word, born of the Father before time began, and

one in substance with the Father, homoousios to Patri, and through him all

things were made. He was incarnate of the Virgin Mary by the power of the

Holy Spirit, and was made man: equal therefore to the Father according to his

divinity, and inferior to the Father according to his humanity and himself one,

not by some impossible confusion of his natures, but by the unity of his person."

"In the beginning": "what this means is that he always was, and that he is

eternal. [...] For if he is God, as indeed he is, there is nothing prior to him; if

he is creator of all things, then he is the First; if he is Lord of all, then everything

comes after him -- created things and time" (St John Chrysostom, Hom. on St

John, 2, 4).

"In the beginning": "what this means is that he always was, and that he is

eternal. [...] For if he is God, as indeed he is, there is nothing prior to him; if

he is creator of all things, then he is the First; if he is Lord of all, then everything

comes after him -- created things and time" (St John Chrysostom, Hom. on St

John, 2, 4).

3. After showing that the Word is in the bosom of the Father, the prologue

goes on to deal with his relationship to created things. Aiready in the Old

Testament the Word of God is shown as a creative power (cf. Is 55:10-11), as

Wisdom present at the creation of the world (cf. Prov 8:22-26). Now Revelation

is extended: we are shown that creation was caused by the Word; this does

not mean that the Word is an instrument subordinate and inferior to the Father: he

is an active principle along with the Father and the Holy Spirit. The work of

creation is an activity common to the three divine Persons of the Blessed

Trinity: "the Father generating, the Son being born, the Holy Spirit proceeding;

consubstantial, co-equal, co-omnipotent and co-eternal; one origin of all things:

the creator of all things visible and invisible, spiritual and corporal." (Fourth

Lateran Council, De fide catholica, Dz-Sch, 800). From this can be deduced,

among other things, the hand of the Trinity in the work of creation and,

therefore, the fact that all created things are basically good.

4. The prologue now goes on to expound two basic truths about the

Word -- that he is Life and that he is Light. The Life referred to here is divine

life, the primary source of all life, natural and supernatural. And that Life is the

light of men, for from God we receive the light of reason, the light of truth and

the light of glory, which are a participation in God's mind. Only a rational

creature is capable of having knowledge of God in this world and of later

contemplating him joyfully in heaven for all eternity. Also the Life (the Word)

is the light of men because he brings them out of the darkness of sin and error

(Cf. Is 8:23; 9:1-2; Mt 4:15-16; Lk 1:74). Later on Jesus will say: "I am the light

of the world; he who follows me will not walk in darkness, but will have the

Iight of life" (Jn 8:12; cf. 12:46).

Vv. 3 and 4 can be read with another punctuation, now generally abandoned

but which had its supporters in ancient times: "All things were made through

him, and without him nothing was made; insofar as anything was made in him,

he was the life and the life was the light of men." This reading would suggest

that everything that has been created is life in the Word, that is, that all things

receive their being and activity, their life, through the Word: without him they

cannot possibly exist.

5. ["And the darkness comprehended it not." Divine Worship: The Missal]

"And the darkness has not overcome it": the original Greek verb, given

in Latin as comprehenderunt, means to embrace or contain as if putting one's

arms around it -- an action which can be done with good dispositions (a friendly

embrace) or with hostility (the action of smothering or crushing someone). So

there are two possible translations: the former is that given in the Navarre

Spanish, the latter that in the RSV. The RSV option would indicate that Christ

and the Gospel continue to shine among men despite the world's opposition,

indeed overcoming it, as Jesus later says: "Be of good cheer: I have overcome

the world" (Jn 16:33; cf. 12:31; 1 Jn 5:4). Either way, the verse expresses the

darkness' resistance to, repugnance for, the light. As his Gospel proceeds, St

John explains further about the light and darkness: soon, in vv. 9-11, he refers

to the struggle between them; later he will describe evil and the powers of the

evil one, as a darkness enveloping man's mind and preventing him from

knowing God (cf. Jn 12:15-46; 1 Jn 5:6).

St Augustine (In Ioann. Evang., 1, 19) comments on this passage as follows:

"But, it may be, the dull hearts of some cannot yet receive this light. Their sins

weigh them down, and they cannot discern it. Let them not think, however, that,

because they cannot discern it, therefore it is not present with them. For they

themselves, because of their sins, are darkness. Just as if you place a blind

person in the sunshine, although the sun is present to him, yet he is absent from

the sun; in the same way, every foolish man, every unrighteous man, every

ungodly man, is blind in heart. [...] What course then ought such a one to take?

Let him cleanse the eyes of his heart, that he may be able to see God. He will

see Wisdom, for God is Wisdom itself, and it is written: `Blessed are the clean

of heart, for they shall see God.'" There is no doubt that sin obscures man's

spiritual vision, rendering him unable to see and enjoy the things of God.

6-8. After considering the divinity of the Lord, the text moves on to deal

with his incarnation, and begins by speaking of John the Baptist, who makes

his appearance at a precise point in history to bear direct witness before man

to Jesus Christ (Jn 1:15, 19-36; 3:22ff). As St Augustine comments: "For as

much as he [the Word Incarnate] was man and his Godhead was concealed,

there was sent before him a great man, through whose testimony He might be

found to be more than man" (In Ioann. Evang., 2, 5).

All of the Old Testament was a preparation for the coming of Christ. Thus,

the patriarchs and prophets announced, in different ways, the salvation the

Messiah would bring. But John the Baptist, the greatest of those born of woman

(cf. Mt 11:11), was actually able to point out the Messiah himself; his testimony

marked the culmination of all the previous prophecies.

So important is John the Baptist's mission to bear witness to Jesus Christ

that the Synoptic Gospels start their account of the public ministry with John's

testimony. The discourses of St Peter and St Paul recorded in the Acts of the

Apostles also refer to this testimony (Acts 1:22; 10:37; 12:24). The Fourth

Gospel mentions it as many as seven times (1:6, 15, 19,29,35; 3:27; 5:33). We

know, of course, that St John the Apostle was a disciple of the Baptist before

becoming a disciple of Jesus, and that it was in fact the Baptist who showed

him the way to Christ (cf. 1:37ff).

The New Testament, then, shows us the importance of the Baptist's mission,

as also his own awareness that he is merely the immediate Precursor of the

Messiah, whose sandals he is unworthy to untie (cf. Mk 1:7): the Baptist stresses

his role as witness to Christ and his mission as preparer of the way for the

Messiah (cf. Lk 1:15-17; Mt 3:3-12). John the Baptist's testimony is undiminished

by time: he invites people in every generation to have faith in Jesus,

the true Light.

9. "The true light..." [the Spanish translation of this verse is along these

lines: "It was the true light that enlightens every man who comes into the

world."]; the Fathers, early translations, and most modern commentators see

"the Word" as being the subject of this sentence, which could therefore be

translated as "the Word was the true light that enlightens every man who comes

into the world ...". Another interpretation favoured by many modem scholars

makes "the light" the subject, in which case it would read "the true light existed,

which enlightens ...". Either way, the meaning is much the same.

"Coming into the world": it is not clear in the Greek whether these words

refer to "the light", or to "every man". In the first case it is the Light (the Word)

that is coming into this world to enlighten all men; in the second it is the men

who, on coming into this world, on being born, are enlightened by the Word;

the RSV and the new Vulgate opt for the first interpretation.

The Word is called "the true light" because he is the original light from which

every other light or revelation of God derives. By the Word's coming, the world

is fully lit up by the authentic Light. The prophets and all the other messengers

of God, including John the Baptist, were not the true light but his reflection,

attesting to the Light of the Word.

A propos the fullness of light which the Word is, St John Chrysostom asks:

"If he enlightens every man who comes into the world, how is it that so many

have remained unenlightened? For not all, to be sure, have recognized the high

dignity of Christ. How, then, does he enlighten every man? As much as he is

permitted to do so. But if some, deliberately closing the eyes of their minds, do

not wish to receive the beams of this light, darkness is theirs. This is not because

of the nature of the light, but is a result of the wickedness of men who

deliberately deprive themselves of the gift of grace" (Hom. on St John, 8, 1).

10. The Word is in this world as the maker who controls what he has made

(cf. St Augustine, In Ioann. Evang., 2, 10). In St John's Gospel the term "world"

means "all creation, all created things (including all mankind)": thus, Christ

came to save all mankind: "For God so loved the world that he gave his only

Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life. For

God sent the Son into the world, not to condemn the world, but that the world

might be saved through him" (Jn 3:16-17). But insofar as many people have

rejected the Light, that is, rejected Christ, "world" also means everything

opposed to God (cf. Jn 17:14-15). Blinded by their sins, men do not recognize

in the world the hand of the Creator (cf. Rom 1:18-20; Wis 13:1-15): "they

become attached to the world and relish only the things that are of the world"

(St John Chrysostom, Hom. on St John, 7). But the Word, "the true light", comes

to show us the truth about the world (cf. Jn 1:3; 18:37) and to save us.

11. "his own home, his own people": this means, in the first place, the

Jewish people, who were chosen by God as his own personal "property", to be

the people from whom Christ would be born. It can also mean all mankind, for

mankind is also his: he created it and his work of redemption extends to

everyone. So the reproach that they did not receive the Word made man should

be understood as addressed not only to the Jews but to all those who rejected

God despite his calling them to be his friends: "Christ came; but by a mysterious

and terrible misfortune, not everyone accepted him. [...] It is the picture of

humanity before us today, after twenty centuries of Christianity. How did this

happen? What shall we say? We do not claim to fathom a reality immersed in

mysteries that transcend us -- the mystery of good and evil. But we can recall

that the economy of Christ, for its light to spread, requires a subordinate but

necessary cooperation on the part of man -- the cooperation of evangelization,

of the apostolic and missionary Church. If there is still work to be done, it is all

the more necessary for everyone to help her" (Paul VI, General Audience, 4

December 1974).

12. Receiving the Word means accepting him through faith, for it is through

faith that Christ dwells in our hearts (cf. Eph 3:17). Believing in his name means

believing in his Person, in Jesus as the Christ, the Son of God. In other words,

"those who believe in his name are those who fully hold the name of Christ,

not in any way lessening his divinity or his humanity" (St Thomas Aquinas,

Commentary on St John,in loc.).

"He gave power [to them]" is the same as saying "he gave them a free

gift" -- sanctifying grace -- "because it is not in our power to make ourselves

sons of God" (ibid.). This gift is extended through Baptism to everyone,

whatever his race, age, education etc. (cf. Acts 10:45; Gal 3:28). The only

condition is that we have faith.

"The Son of God became man", St Athanasius explains, "in order that the

sons of men, the sons of Adam, might become sons of God. [...] He is the Son

of God by nature; we, by grace" (De Incarnatione contra arrianos). What is

referred to here is birth to supernatural life: in which "Whether they be slaves

or freemen, whether Greeks or barbarians or Scythians, foolish or wise, female

or male, children or old men, honourable or without honour, rich or poor, rulers

or private citizens, all, he meant, would merit the same honour. [...] Such is

the power of faith in him; such the greatness of his grace" (St John Chrysostom,

Hom. on St John,10, 2).

"Christ's union with man is power and the source of power, as St John stated

so incisively in the prologue of his Gospel: `(The Word) gave power to become

children of God.' Man is transformed inwardly by this power as the source of

a new life that does not disappear and pass away but lasts to eternal life (cf. Jn

4:14)" (John Paul II, Redemptor hominis, 18).

13. The birth spoken about here is a real, spiritual type of generation which

is effected in Baptism (cf. 3:6ff). Instead of the plural adopted here, referring

to the supernatural birth of men, some Fathers and early translations read it in

the singular: "who was born, not of blood... but of God", in which case the

text would refer to the eternal generation of the Word and to Jesus' generation

through the Holy Spirit in the pure womb of the Virgin Mary. Although the

second reading is very attractive, the documents (Greek manuscripts, early

translations, references in the works of ecclesiastical writers, etc.) show the

plural text to be the more usual, and the one that prevailed from the fourth

century forward. Besides, in St John's writings we frequently find reference to

believers as being born of God (cf. Jn 3:3-61 Jn 2:29; 3:9; 4:7; 5:1,4, 18).

The contrast between man's natural birth (by blood and the will of man) and

his supernatural birth (which comes from God) shows that those who believe

in Jesus Christ are made children of God not only by their creation but above

all by the free gift of faith and grace.

14. This is a text central to the mystery of Christ. It expresses in a very

condensed form the unfathomable fact of the incarnation of the Son of God.

"When the time had fully come, God sent forth his Son, born of woman" (Gal

4:4).

The word "flesh" means man in his totality (cf. Jn 3:6; 17:2; Gen 6:3; Ps

56:5); so the sentence "the Word became flesh" means the same as "the Word

became man." The theological term "incarnation" arose mainly out of this text.

The noun "flesh" carries a great deal of force against heresies which deny that

Christ is truly man. The word also accentuates that our Saviour, who dwelt

among us and shared our nature, was capable of suffering and dying, and it

evokes the "Book of the Consolation of Israel" (Is 40:1-11), where the fragility

of the flesh is contrasted with the permanence of the Word of God: "The grass

withers, the flower fades; but the Word of our God will stand for ever" (Is 40:8).

This does not mean that the Word's taking on human nature is something

precarious and temporary.

"And dwelt among us": the Greek verb which St John uses originally means

"to pitch one's tent", hence, to live in a place. The careful reader of Scripture

will immediately think of the tabernacle, or tent, in the period of the exodus

from Egypt, where God showed his presence before all the people of Israel

through certain sights of his glory such as the cloud covering the tent (cf., for

example, Ex 25:8; 40:34-35). In many passages of the Old Testament it is

announced that God "will dwell in the midst of the people" (cf., for example,

Jer 7:3; Ezek 43:9; Sir 24:8). These signs of God's presence, first in the pilgrim

tent of the Ark in the desert and then in the temple of Jerusalem, are followed

by the most wonderful form of God's presence among us -- Jesus Christ, perfect

God and perfect Man, in whom the ancient promise is fulfilled in a way that

far exceeded men's greatest expectations. Also the promise made through

Isaiah about the "Immanuel" or "God-with-us" (1s 7:14; cf. Mt 1:23) is

completely fulfilled through this dwelling of the Incarnate Son of God among

us. Therefore, when we devoutly read these words of the Gospel `and dwelt

among us" or pray them during the Angelus, we have a good opportunity to

make an act of deep faith and gratitude and to adore our Lord's most holy human

nature.

"Remembering that `the Word became flesh', that is, that the Son of God

became man, we must become conscious of how great each man has become

through this mystery, through the Incarnation of the Son of God! Christ, in fact,

was conceived in the womb of Mary and became man to reveal the eternal love

of the Creator and Father and to make known the dignity of each one of us"

(John Paul II, Angelus Address at Jasna Gora Shrine, 5 June 1979).

Although the Word's self-emptying by assuming a human nature concealed

in some way his divine nature, of which he never divested himself, the Apostle

did see the glory of his divinity through his human nature: it was revealed in

the transfiguration (Lk 9:32-35), in his miracles (Jn 2:11; 11:40), and especially

in his resurrection (cf. Jn 3:11; 1 Jn 1:1). The glory of God, which shone out in

the early tabernacle in the desert and in the temple at Jerusalem, was nothing

but an imperfect anticipation of the reality of God's glory revealed through the

holy human nature of the Only-begotten of the Father. St John the Apostle

speaks in a very formal way in the first person plural: "we have beheld his

glory", because he counts himself among the witnesses who lived with Christ

and, in particular, were present at his transfiguration and saw the glory of his

resurrection.

The words "only Son" ("Only-begotten") convey very well the eternal and

unique generation of the Word by the Father. The first three Gospels stressed

Christ's birth in time; St John complements this by emphasizing his eternal

generation.

The words "grace and truth" are synonyms of "goodness and fidelity", two

attributes which, in the Old Testament, are constantly applied to Yahweh (cf.,

e.g., Ex 34:6; Ps 117; Ps 136; Hos 2:16-22): so, grace is the expression of

God's love for men, the way he expresses his goodness and mercy. Truth

implies permanence, loyalty, constancy, fidelity. Jesus, who is the Word of God

made man, that is, God himself, is therefore "the only Son of the Father, full

of grace and truth"; he is the "merciful and faithful high priest" (Heb 2:17).

These two qualities, being good and faithful, are a kind of compendium or

summary of Christ's greatness. And they also parallel, though on an infinitely

lower level, the quality essential to every Christian, as stated expressly by our

Lord when he praised the "good and faithful servant" (Mt 25:21).

As Chrysostom explains: "Having declared that they who received him were

`born of God' and `become sons of God,' he then set forth the cause and reason

for this ineffable honour. It is that `the Word became flesh' and the Master took

on the form of a slave. He became the Son of Man, though he was the true Son

of God, in order that he might make the sons of men children of God. (Hom.

on St John, 11,1).

The profound mystery of Christ was solemnly defined by the Church's

Magisterium in the famous text of the ecumenical council of Chalcedon (in the

year 451): "Following the holy Fathers, therefore, we all with one accord teach

the profession of faith in the one identical Son, our Lord Jesus Christ. We

declare that he is perfect both in his divinity and in his humanity, truly God and

truly man, composed of body and rational soul; that he is consubstantial with

the Father in his divinity, consubstantial with us in his humanity, like us in

every respect except for sin (cf. Heb 4:15). We declare that in his divinity

he was begotten of the Father before time, and in his humanity he was begotten

in this last age of Mary the Virgin, the Mother of God, for us and for our

salvation." (Dz-Sch, n. 301).

ISBN 978-1-85182-094-8

"In the beginning": "what this means is that he always was, and that he is

eternal. [...] For if he is God, as indeed he is, there is nothing prior to him; if

he is creator of all things, then he is the First; if he is Lord of all, then everything

comes after him -- created things and time" (St John Chrysostom, Hom. on St

John, 2, 4).

"In the beginning": "what this means is that he always was, and that he is

eternal. [...] For if he is God, as indeed he is, there is nothing prior to him; if

he is creator of all things, then he is the First; if he is Lord of all, then everything

comes after him -- created things and time" (St John Chrysostom, Hom. on St

John, 2, 4).

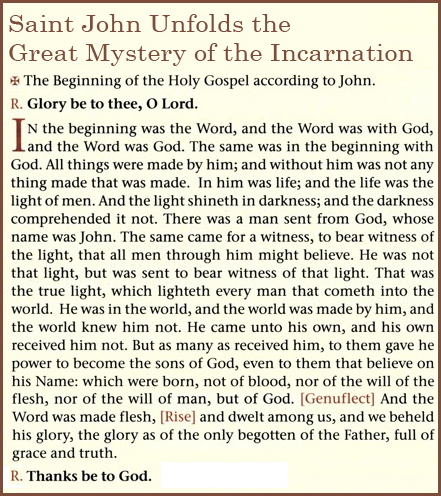

St John unfolds the great mystery of the Incarnation.

St John unfolds the great mystery of the Incarnation.